Amazing Stories

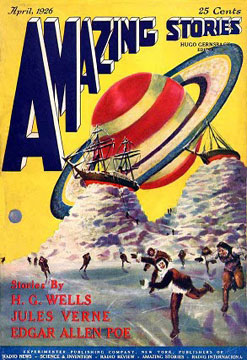

In April 1926, a Luxembourgian-American inventor and electrical enthusiast, Hugo Gernsback, published his inaugural issue of Amazing Stories, the first and longest-running English-language magazine dedicated to what was then not quite yet called "science fiction"—a field it would, for better and for worse, define for the modern era.

What is most surprising about Amazing Stories is that it took so long for a magazine of its type to appear. For decades, tales of scientific gadgetry and romance had been filling periodical pages in England, France, and America, and many related subgenres had received exclusive outlets long before Gernsback provided one for "scientifiction."

In the foreword to Amazing's first number, Gernsback introduced his "New Sort of Magazine," geared as he said to the "entirely new world" of the modern. He cited as his forebears Edgar Allen Poe, Jules Verne, and H.G. Wells—or the "new romancers," in a phrase that would later catch William Gibson's attention—and delineated a literary form aiming to instruct as well as entertain, to "impart knowledge … without once making us aware that we are being taught."

For all his namedropping, Gernsback took the greater share of his inspiration from his own previous forays into publishing. His editorial career began in 1908 with Modern Electrics, a magazine aiming "to teach the young generation science, radio and what was ahead for them." It was here that he first started serializing scientifiction—his own novel, Ralph 124C41+—before selling up and founding The Electrical Experimenter. In these magazines, as later in Amazing Stories, Gernsback laid down a blueprint for the capitalist technocracies of the future, to be led by daring inventors such as his own Ralph, modeled after Thomas Edison.

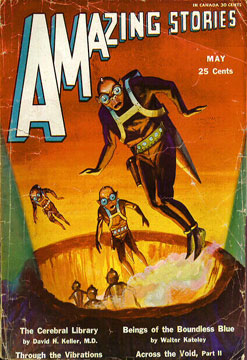

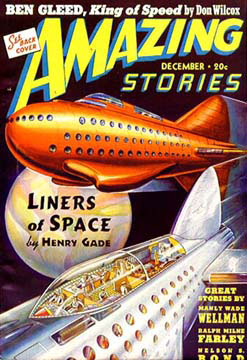

Gernsback's future has dated badly—see Gibson's "The Gernsback Continuum"—but his vision, aided by eyepopping cover illustrations by Frank R. Paul, was sufficiently inspiring to draw an extensive community of readers—many of whom came to write SF stories after serving an apprenticeship of sorts sending letters to the magazine's "Discussions" section. In this communal relationship are the roots of SF's subsequent insularity and ghettoization, as well as the first glimmerings of the genre's Golden Age. Amazing and Gernsback would largely miss the latter; though he published such early standouts as Murray Leinster and E.E. Smith, increasing perception of the magazine as garish and nonliterary—not to mention Gernsback's extreme reluctance to pay his authors competitive rates, or at all—led to the magazine changing hands in 1929.

Gernsback moved on to other projects, but Amazing surprisingly soldiered, with the magazine even giving a debut to the man who succeeded Gernsback as SF generalissimo: John W. Campbell. But while Campbell was laying the groundwork for his later dominance of the field, Amazing floundered and, ceding to economic reality, finally went pulp in mid-1933 after years of monthly publication on large-format heavy stock.

In 1938 Ziff-Davis bought the title and appointed a new editor, Raymond A. Palmer, from the ranks of SF fandom. Throughout Palmer's editorship, Amazing relied on a core of steady, unspectacular contributions, livened occasionally by the likes of a Ray Bradbury or Eric Frank Russell (as well as a series of Edgar Rice Burroughs novellas). This would change radically, however, with the advent of the Shaver Mystery. Like many SF authors, Richard Shaver first saw print in Amazing's correspondence section; unlike those others, he presented his narratives as absolute fact: records of his past lives on lost continents, as well as his torture at the hands of devolved beings living underground. Reader response was overwhelming, many claiming they, too, remembered previous incarnations; catering to these devotees meant Amazing effectively becoming a house organ for Shaver material.

Those still devoted to Gernsback's model of a more educational form of fiction abandoned the magazine, until Palmer eventually left to document similar weird phenomena in Fate. New editor Harold Browne set out in 1950 to completely change Amazing's image but Korean War cutbacks made this plan unworkable. Stories from Isaac Asimov, Fritz Leiber, Arthur C. Clarke, and other luminaries did briefly make Amazing a legitimate outlet for many of the genre's best, but even Browne's more modest changes didn't quite take, and he increasingly shifted attention to a companion magazine, Fantastic. Unable to compete for authors with Campbell's Astounding or newer competitors, Amazing again looked doomed—but recovered, this time under editor Cele Goldsmith.

Goldsmith brought back in authors such as Asimov and Cordwainer Smith, and also printed early stories from writers of the soon-to-be-labeled New Wave, among them Ursula Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, and J.G. Ballard. But just as it appeared ready to shape science fiction all over again, the magazine was hobbled: sold off to a competitor who turned it into a reprint outlet, an echo chamber of its former self. After some years, the editorship stabilized under SF fan and artist Ted White. Fittingly, White revamped Amazing's image, updating the art and layout, extending the magazine's relationship with Dick and Le Guin, and developing new voices such as James Tiptree, Jr.

But after a decade, White could no longer fight the magazine's publisher. He resigned and the decision was made to fold Amazing in with its longsuffering shadow, Fantastic; despite considerable efforts by editor Elinor Mavor, the magazine was sold in 1982 to Gary Gygax of D&D fame, and would never again regain the prominence it had before. Though after March 2005 Amazing ceased publication, after several abortive attempts at relaunching, the trademark remains alive, and the magazine may yet revive online. But the days of print publication now seem past for this institution—one of the few to significantly shape the 20th century and survive (however briefly) the coming of the 21st.

Andrew Ferguson, University of Virginia

Works Cited and Consulted

Ashley, Mike. The Story of the Science Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950, 3 vol. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 2000–2007.

___ and Robert A.W. Lowndes. The Gernsback Days. Gillette, N.J.: Wildside Press, 2004.

Csicsery-Ronay, Jr., Istvan. "Science Fiction/Criticism." A Companion to Science Fiction. Ed. David Seed. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Publishing, 2008. 43–59.

Gernsback, Hugo. "A New Sort of Magazine." Amazing Stories 1:1 (April 1926). 3.

Westfahl, Gary. The Mechanics of Wonder: The Creation of the Idea of Science Fiction. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 1998.