Beau Collier's "Birth of the Girlie Pulps"

Featured below is an essay by popular print historian Beau Collier. It is reprinted by permission of the author from an earlier version on publisher Frank Armer and the girlie pulps, which first appeared on Collier's blog, Darwination Scans. Paired with the essay are representative issues of snappy, spicy, & girlie pulps of the 1930s and 40s, including 10 Story Book, Follies, Gay Life Stories, Ginger Stories, Hollywood Nights, La Paree, Night Life Tales, Pep Stories, Snappy, and Spicy Stories. To access these issues, click on the link below. The Pulp Magazines Project wishes to thank Mr. Collier for his scans, and for permission to reprint his essay. NOTE: All cover scans are the © of their respective owners and/or creators.

For issues of snappy, spicy, and "girlie" pulps from the 1930s and 1940s, click here.

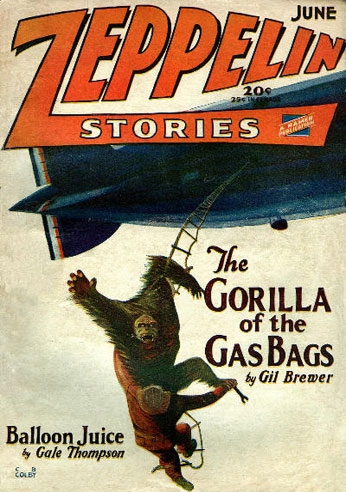

In 1912, circulation manager W. M. Clayton left The Smart Set to establish his own magazine, Snappy Stories. One of the original examples of a "girlie" pulp, Snappy Stories was a somewhat risqué publication for its time. It published stories touching upon the subject of pre-marital sex, with illustrations of scantily clad women. The flirtatious GGA covers attracted attention on newsstands. The magazine’s popularity encouraged several imitators, which by the end of WWI included The Parisienne (1915), Breezy Stories (1915), and Saucy Stories (1916); although Young’s Magazine (1897) was perhaps the first such magazine devoted largely to sex-themed stories, issues printed on pulp paper did not appear until early 1917. Telling Tales debuted in 1919; and "I Confess" was introduced as a bi-weekly in 1922. Among the second generation of publishers to capitalize on the genre's appeal through the 1920s was Frank Armer, who became the leading publisher of girlie pulps by the end of the decade. He is probably best known today as the editor of the notorious Culture/Trojan line of Spicy pulps, or as publisher of the notoriously short-lived Zeppelin Stories. Armer's chief contribution to magazine culture, however, was as a pioneer in the popular movie, art photo, and girlie magazines of the period between the world wars.

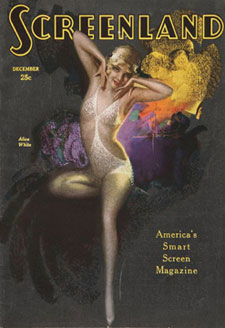

Little is known about Armer before he entered the magazine publishing business as a force behind Screenland, which was a Hollywood-based competitor to the burgeoning field of popular movie magazines published at the time, such as Street & Smith’s Picture-Play, or Bernarr MacFadden’s Photoplay—which boasted a million plus circulation in 1922.

Armer was a bohemian personality with an artistic bent, and he came of age with Hollywood itself. In the early 1920s, he worked as an assistant director for Sam Wood, and alongside celebrities such as Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson, and Wallace Reed. At the time, Screenland was struggling with its distribution, which was handled through the News Co., and under Armer’s direction the magazine went independent, and built a national distribution with the help of Paul Sampliner, who was Armer’s business manager. Sampliner later founded Eastern News Co., a major magazine distributor by the end of the decade. The printing company that handled all the covers for Screenland, Donny Press, employed Harry Donenfeld as head of its promotions department. Donenfeld became the largest publisher of girlie pulps in the 1930s, and a founding force behind National Allied Publications in 1934, the company which later became known as DC comics.

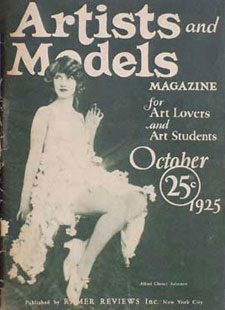

By 1925, Armer had sold out his interest in Screenland and was splitting his time between New York and San Francisco, working as an agent for a number of printing companies, including the Donny Press, and affiliated with Eastern News. Not satisfied with his role as agent, Armer began his own type of magazine that captured the raucousness of the roaring 1920s, Artists and Models, which carried the subtitle "For Art Lovers and Art Students." Page images from the Oct. 1925 issue are shown below:

Many of the models were nudes or draped nudes. Some were dressed in exotic costumes. Subjects included movie stars, Hollywood starlets, artists' models, dancers, and show girls—along with articles on artistic subjects, the movies, and risqué humor. There were also full page illustrations of great works of art, most featuring classic nudes, including paintings such as "Centaurs at Play" by Wilhelm Trubner. Armer had connections with California photographers like Edwin Bower Hesser, whose nude studies also found their way into Screenland, and with the Hollywood and Broadway starlets who appeared in this peculiar type of magazine (Joan Crawford is featured in the February 1926 issue, for example).

Alongside re-creations of the classics, poetry, theatre reviews, and art deco illustrations were nude flappers thusly secreted past the post office censors. Donenfeld printed Armer’s covers and photo pages—often very high-quality printings on slick paper—in sepias, greens, and deep, glossy reds. He took to Armer and the enterprise so well, before long he was helping to launch new titles—most of them devoted to the edification of shapely forms—like Art and Beauty, Art Photos, World of Art, French Art Classics, Modern Art, Art Studies, and Fine Arts Quarterly. Doubtless, there were others too.

__

__

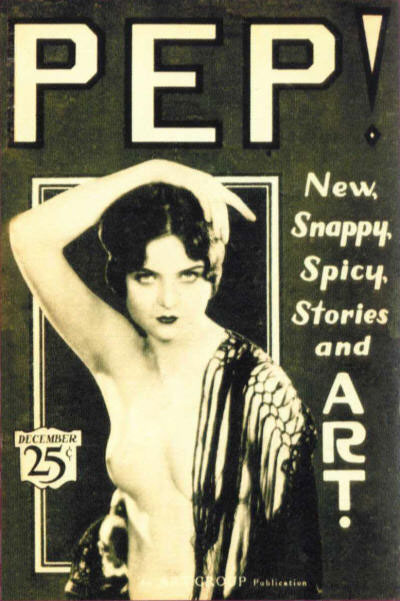

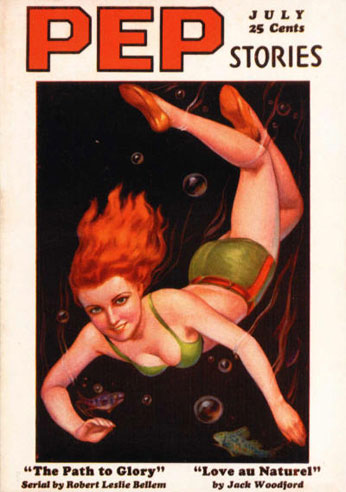

Launched in December 1926, Pep! was a hybrid magazine, and pointed in the direction that Armer would take for the rest of the decade. Eschewing any phony art angles, Pep! mixed nude photos with breezy jokes ala the popular gag and humor magazines; illustrations were risqué but artful—after the manner of the first girlie pulps to venture into naughty territory, like Snappy Stories—and issues contained a fast brand of fiction that proved popular with readers, i.e. the romantic screwball comedy with a love interest. Plots developed quickly, slang and modern phrases were bandied about, and boy gets girl but never quite gets girl. In fact, real sex was absolutely avoided. The formula was romance, but without the drama of the love pulps. It was geared towards comedy. The stories were usually short, the conventions were always flaunted, and the battle of the sexes never stopped.

Artists like Jack Woodford and Robert Leslie Bellem made names for themselves in these stories. Others used pen names, or house names would be assigned to them. Today, tracking down authors to some of these stories is nearly impossible. A good number of these authors were female, while letter columns indicate, at least partly, a female readership. And many of the girlie pulps were edited by women. Armer's line, for example, was initially edited by Natalie Messenger; when she left, Cecile Glassberg took over. So it may not have just been male readers who ventured into the pages of the "smoosh" pulps.

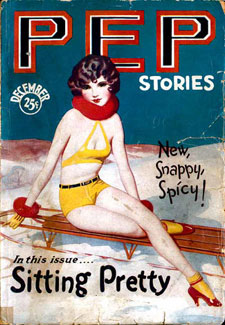

Due to the enormous response from the newsstands with Pep!—and Armer's realization that readers preferred the stories in these pulps most of all—the magazine was retitled Pep Stories by its May 1927 issue. It dropped the nude photos, and changed from a saddle-stitched, slick format to a conventional pulp format. Pep Stories continued publication for over a decade, and totalled approximately 150 issues, becoming the longest-lived of this variety of girlie pulp.

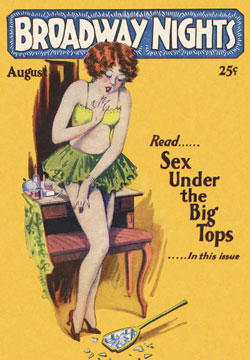

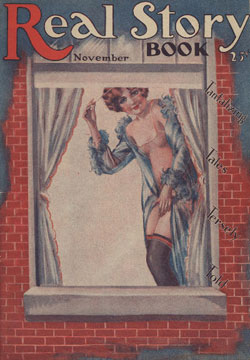

The next girlie pulp Armer brought out was Broadway Nights, which debuted in July 1928. This was a smaller, saddle-stitched pulp with lower production values than Pep Stories, and it became the model for both Ginger Stories and Real Story Book which debuted in November that same year. These three titles seemingly shared the same authors, artists, and editor; since their look and feel are largely interchangeable. These four titles were joined by a fifth, longer-lasting girlie pulp in Armer’s stable, Spicy Stories, which debuted as a square-bound bedsheet pulp in December 1928. Spicy Stories, like Pep Stories, remained in publication until the late 1930s. Reflecting the higher production values and popularity of these champions of longevity, Pep Stories and Spicy Stories paid 1 1/2 cents per word for fiction on publication—which was well above the industry standard—while Broadway Nights, Ginger Stories, and Real Story Book paid only 1 cent per word on publication (still a better rate than most of Armer's competitors).

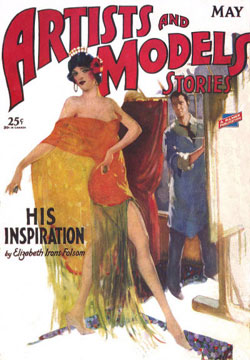

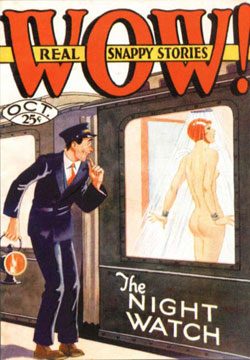

But the pace of American magazine production in the 1920s—which put more than 2,000 magazine issues in print at any given time—was hit hard by the stock market crash of 1929; and Armer's own fortunes slowed with the onset of the great depression. His subsequent girlie pulp titles, Artists and Model Stories (2 issues in 1929, bedsheet format) and Wow! (5 issues from 1930-31, pulp format) did not get off the ground.

__

__

__

__

A further sign of the downturn in Armer’s fortunes was a decrease in pay rates. By mid-1930, Armer had reduced the rate paid to contributors to Spicy Stories and Pep Stories to 1 cent per word; and to 3/4 cents per word on other titles. In 1931, he began experimenting with title changes, usually a sign of flagging sales. Ginger Stories was shortened to Ginger (See Note 1), while Real Story Book changed names at least three times—from Real Story Book–Frolics to Frolics to Paris Frolics—in just over a handful of issues. Complicating Armer's finances was his participation in the stock market; or so the author of a retrospective essay on Armer's career, published in Independent News in 1944, suggested:

Big money was rolling around Wall Street, and Frank decided to go down and collect his share. From 1929 until 1932 he was a Wall Street operator. Look at those dates again, and you can figure out what happened to Frank there. ("Close Up")

In any case, the last issues of Ginger and Real Story Book-turned-French Frolics were published in April 1932; and the last issue seen for Broadway Nights is the February 1932 issue. In May 1932, Armer surrendered the gems of his line, Pep Stories and Spicy Stories, to Harry Donenfeld for printing debts owed; in like manner, Donenfeld accrued many girlie pulp titles during the 1930s. It was the same tactic (though perhaps in less-friendly form) that led to Donenfeld's takeover of the rights to Superman and other comic book properties from Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson in 1938. Bowing out gracefully, Armer did Donenfeld an additional service by making a ploy to deflect the censors part of the deal.

In spring 1932, the New York Committee on Civic Decency had pressured the police to arrest four newsstand owners for selling girlie pulps. At a July meeting with the Committee, charges against the four owners were dropped after Armer and other editors promised to "tone-down" their content and "pay closer heed to the proprieties"—as well as cease publication of Ginger Stories, Hollywood Nights, Gay Broadway, Broadway Nights, French Follies, and La Paree. Donenfeld continued to print La Paree in spite of this agreement, and in addition to Ginger and Broadway Nights, Armer probably had a controlling interest in Henry Marcus’ (Pictorial) French Follies and Hollywood Nights. So Armer's pulps, which were going out of business in any case, became the sacrificial lambs, while newsstand owners were off the hook—at least for the time being.

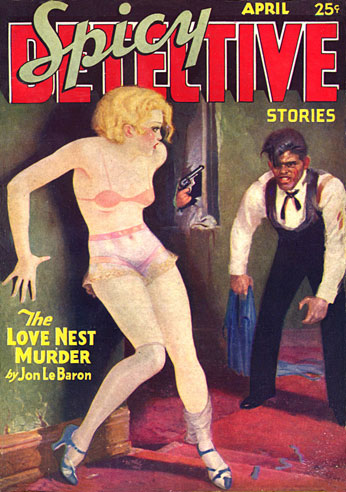

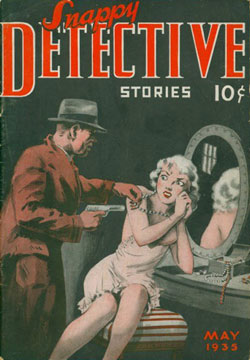

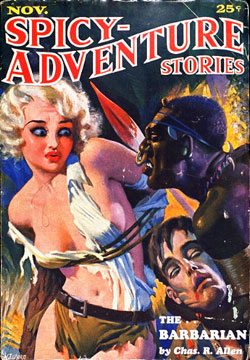

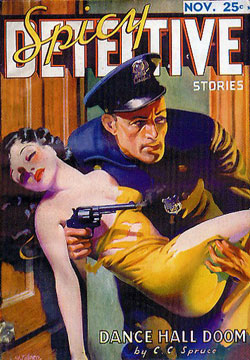

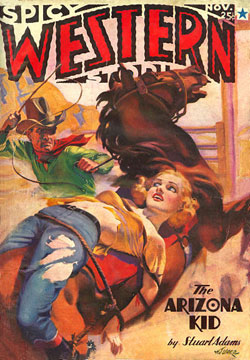

Thus, Armer's career as a girlie pulp publisher ended—although he would still have a long career in the pulps ahead of him (and perhaps even some minority-shares in various publications) when he came to work for Donenfeld in late 1933. In his role as Editor-in-Chief for Donenfeld, Armer continued to work with many of the authors and artists who had contributed to his own pulps. He gave Donenfeld the idea of melding the girlie appeal of the smoosh pulps with the red-blooded genres of detective, adventure, and Western pulps, which resulted in the popular and financial success of the Culture/Trojan Spicy line, starting with Spicy Detective. Indeed, Armer's talents for selecting stories, choosing cover illustrations, and nurturing authors and artists were key to the success of the Spicy line. Armer crafted the magazines (See Note 2), while Donenfeld promoted and distributed them.

__

__

__

__

Armer remained the editorial hand behind Donenfeld's pulps for nearly a decade, whereas Donenfeld—with the success of Superman and Detective Comics—increasingly sought to distance himself publicly from such unwholesome properties. In response to renewed public outcry over "dirty magazines" in 1938, Donenfeld discontinued his remaining girlie pulp titles, which included La Paree, and in the early 1940s he cleaned up the entire Spicy line. From their January 1943 issues, titles of the "Spicy" pulps were changed to Speed Detective, Speed Mystery, Speed Adventure, and Speed Western. Along with these title changes, the covers and contents of the magazines were also toned down considerably. The "Speed" titles survived for three more years, before folding in 1946. Trojan continued to publish other pulp magazines until around 1950, when the company itself closed down. Armer would go on to a successful career in advertising.

Beau Collier, Darwination Scans

NOTES

1. A second Ginger series, featuring covers from George Quintana, was introduced by Henry Marcus in mid-1935, and ran through mid-1936. These titles are related in name only.

2. Frank Armer's "Sex in Detective Fiction – Do's and Don'ts" (1935), editorial guidelines published by Spicy Detective:

Sex in Detective Fiction – Do's and Don'ts (1935) by Frank Armer, publisher of Spicy Detective magazine 1. In describing breasts of a female character, avoid anatomical descriptions. 2. If it is necessary for the story to have the girl give herself to a man, do not go too carefully into the details. You can lead up to the actual consummation, but leave the rest up to the reader’s imagination. This subject should be handled delicately and a great deal can be done by implication and suggestion. 3. Whenever possible, avoid complete nudity of the female characters. You can have a girl strip to her underwear, or transparent negligee, or nightgown, or the thin torn shred of her garments, but while the girl is alive and in contact with a man, we do not want complete nudity. 4. A nude female corpse is allowable, of course. 5. Also, a girl undressing in the privacy of her own room, but when men are in the action try to keep at least a shred of something on the girls. 6. Do not have men in underwear in scenes with women, and no nude men at all. (Editorial guidelines published by Spicy Detective magazine in 1935). |

|---|

Sources

Clayton, W. M. "An Advertisement the Boss Wrote." Printer's Ink, Vol. 88, No. 10 (Sept. 3, 1914): 61.

Ellis, Doug. Uncovered: The Hidden art of the Girlie Pulps, Silver Springs, Maryland: Adventure House, 2003.

Jones, Gerard. Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book, New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Murray, Will. "DC's Tangled Roots!" Comic Book Marketplace #53, November 1997.

Windy City Pulp Stories #9, 2009, on the Culture/Trojan pulps, esp. Will Murray's articles and "Close Up: Frank Armer – Pulp Potentate" reprinted from Independent News, Vol. 1, 1944.

This essay is here reprinted—by permission of the author—from an earlier version on publisher Frank Armer and the girlie pulps, which first appeared on the author's blog, Darwination Scans. The Pulp Magazines Project wishes to thank Beau Collier for permission to reprint his essay. NOTE: All cover scans are © of their respective owners and/or creators.